Desidirium = nostalgia.

Nostalgia: a wistful or excessively sentimental yearning for return to or of some past period or irrecoverable condition.

The question I’d like to explore: can (the resurgence of) analog photography merely be explained as nostalgic? What is that nostalgia in this context exactly?

I’ve thought about the draft of this post for quite a few months now. I let it rest for weeks, deleted quite a few paragraphs and reminded myself several times not to overthink it, and dare I say it, turn it into a pseudo-intellectual exercise. We like it simple these days, n’est pas?

Since photography’s inception, the camera industry for the consumer market went through these segments with a bell curve that correlated directly with the immense technical innovation of the products, the adoption and growth tied with convenience of use and quality. In general, the consumer products prospered faster and faster from the developments for the professional marketplace, to the point (the arrival of digital cameras) where they eventually merged.

My subjective starting point is the claim that analog photography is one of the most tangible activities to fulfill an innate yearning for nostalgia. But then, how to (objectively) qualify such yearning? I can’t get around the idea of dusting off a scholarly reference point that stuck with me; philosophy. More specifically, Schopenhauer. Which raises the question: can we make ‘nostalgia’ more tangible by picking the brain of a pessimistic, 19th century A-list philosopher? Let me try by borrowing the following:

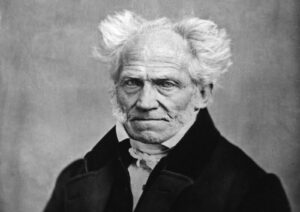

“Arthur Schopenhauer was a German philosopher who developed an immeasurably important work that influenced philosophic tradition as a whole. Extremely influenced by Immanuel Kant and his transcendental idealism, praising Kant’s greatness on many aspects while also heavily criticizing others, Schopenhauer created the extensive metaphysics system described in his magnum opus The World as Will and Representation, and some of the principles of his philosophy present in that book will be integral for us to deeply understand his view on ethics. (Photo: Portrait Photograph of Arthur Schopenhauer by Johann Schäfer, 1859, Frankfurt am Main University Library, Germany, via Wikimedia Commons.)

In the realm of art, photography holds a unique position as a medium that captures moments frozen in time. It not only documents reality but also evokes emotions, memories, and a profound sense of nostalgia. So, with this post I aim to explore the intricate relationship between photography and nostalgia, drawing insights from the philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer.

At its essence, nostalgia is a yearning for the past—a sentimental longing for moments, places, and experiences that are no longer present. It is a bittersweet emotion, blending fondness for what was with the melancholy realization of its irretrievability. Photography, with its ability to preserve moments, becomes a potent vessel for nostalgia. Each photograph acts as a portal, transporting viewers to a specific time and space, inviting them to dwell in memories and emotions long past.

Schopenhauer is known for his emphasis on the primacy of will and the role of art in human experience, he offers a compelling lens through which to view this phenomenon. Central to Schopenhauer’s philosophy is the concept of the Will, an all-encompassing force driving all phenomena in the world. This Will, he argues, is at the core of human desires and sufferings, forever striving and never finding true satisfaction.

In the context of photography and nostalgia, Schopenhauer’s ideas find resonance in the perpetual longing inherent in the human condition. Each nostalgic gaze at a photograph is, in a way, an acknowledgment of the ceaseless striving of the Will. We yearn for the past, not simply because it was a time of joy or contentment, but because it represents a moment when the Will seemed momentarily satisfied. The captured smiles, the fleeting glances frozen in time—all serve as reminders of a time when our desires found a fleeting fulfillment.

Moreover, Schopenhauer’s philosophy sheds light on the paradoxical nature of nostalgia. While it offers a comforting retreat into the past, it also serves as a poignant reminder of life’s transience and the inevitability of change. In “The World as Will and Representation,” Schopenhauer speaks of the fleeting nature of human happiness, likening it to a “soap bubble” that bursts upon contact with reality. This poignant metaphor finds a parallel in the fragile nature of nostalgia evoked by a photograph—a delicate bubble of memory that can be both cherished and mourned.

Photography, as an art form, also aligns with Schopenhauer’s views on the role of art in human life. For Schopenhauer, art serves as a temporary respite from the relentless striving of the Will. It allows us to transcend the individual self and connect with universal truths and emotions. In this sense, a photograph becomes more than a mere representation of reality; it transforms into a medium through which we confront our deepest longings and desires.

As I see it, the relationship between photography and nostalgia unveils a complex interplay of memory, desire, and the relentless striving of the Will. Through Schopenhauer’s philosophical lens, we come to understand that each nostalgic glance at a photograph is not just a yearning for the past but a profound engagement with the essence of human existence. Photography, with its power to freeze moments in time, becomes a testament to our eternal quest for meaning and fulfillment in a world governed by the ceaseless churn of the Will.

As we gaze upon a faded photograph, perhaps of a sunlit afternoon or a fleeting smile, we are confronted with the dualities of nostalgia—its comforting embrace and its poignant reminder of life’s impermanence. In this union of art and philosophy, we find solace in the transient beauty of captured moments, even as we are reminded of the relentless march of time.

Through the lens of Schopenhauer’s philosophy, I come to appreciate photography not just as a means of documentation but as a profound exploration of the human experience—a testament to our eternal longing for moments that slip through our grasp like sand, yet remain forever etched in the fabric of memory.

I enjoy sustained reliefs from the analog process, driven by the paradoxical downsides of the abundance of options with digital photography. One example: the archiving and longevity of analog photography is superior. More labor-intensive, sure, but still superior. In a 100 years it’s more likely to have survived than its digital counterpart. Counter-intuitive, but it’s a fact. (Tip: look up the Efficiency Paradox.) So much for “keeping it simple”, I’m aware, and I don’t claim that my archive is worth 100 years of preservation :-).

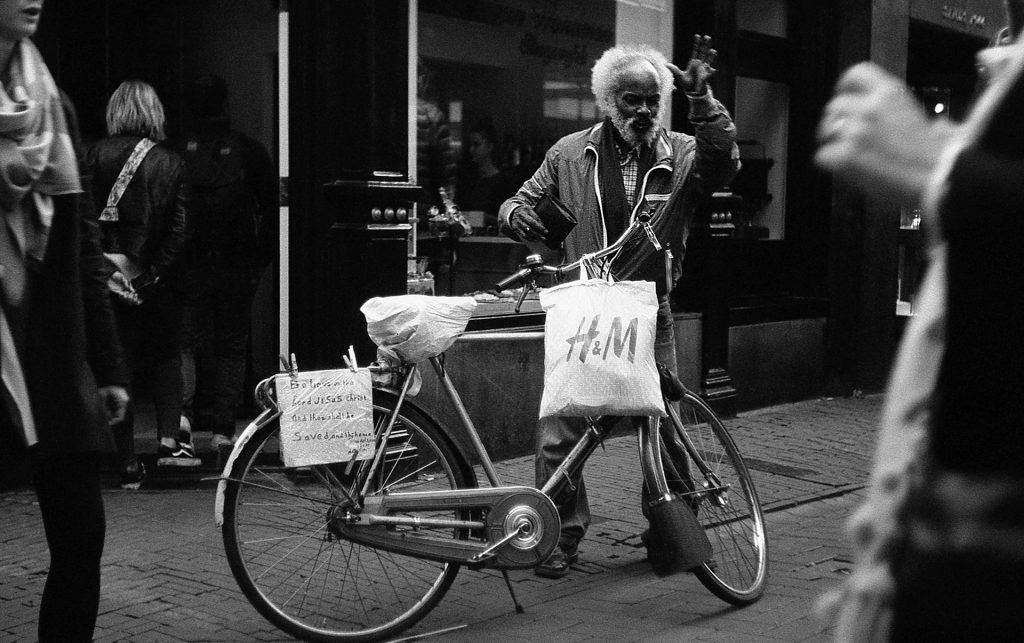

As many before me have uttered, the analog experience forces me to do better, to be more creative, more selective. Which to me, brings more satisfaction. Certainly when I think it’s good enough to hang on my wall. I love and appreciate the craftsmanship and durability of old cameras. I dread but also giddily anticipate the surprises in the development process (at home). I still haven’t mastered my enlarger, but that’s ok, I understand why. I enjoy going through the family archive and discovering negatives to process and surprise my kin with.

I think the latter touches on why I persist with film photography, how I would qualify its use and how ‘nostalgia’ fits into this. At 52, I reconcile that from childhood I’ve always been expressive, with music and imaging. From playing the piano, drawing (pen, charcoal, paint..not many 8 year olds draw life-like portraits without some outside help) to photography (also from 8 years old, Agfa Optima, anyone?) and video. And growing up, for some reason I was always obsessed with the old family archive and the cameras in the back of some boxes. In hindsight, I think that intrigue never faded, no matter how often I would ‘act the child’ and move on to ‘the next thing’. In my formative years I pursued history, education and media in academics, where I gradually shook the hubris of ‘knowing’ and instinctively followed the path of ‘doing’.

Looking back, one notion that stands out is that I was never eager to be photographed (still the case), but the idea to observe others and the world ‘anonymously’ with a camera was absolutely awesome. So, I could summize that growing up with analog photography provided me with very little anguish, but many moments of relief. I suppose the Will persisted positively.

Or… I and many others are clearly delusional;